How did we get into a situation where “the press is lying” and “research is rubbish”?

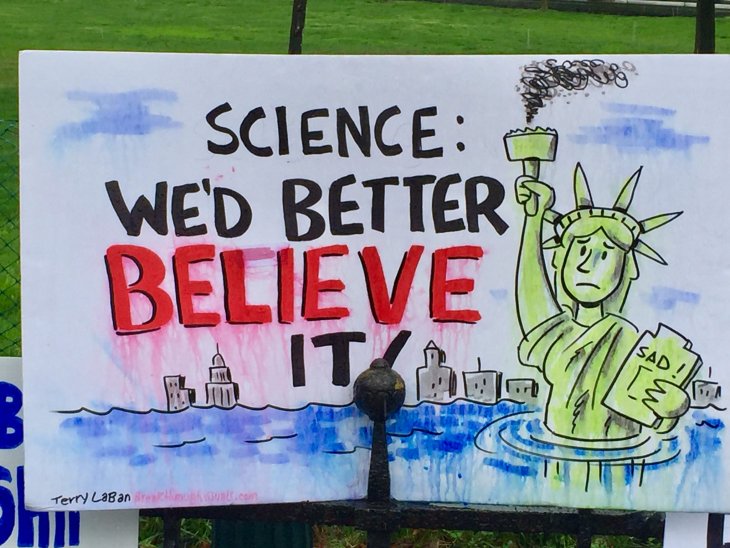

Banner at the March for Science, Washington, D.C. Photo: becker1999 @ Flickr

Society is now experiencing a “storm of distrust” that is “powerful and unpredictable”, with growing resistance to established institutions, if we are to believe the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, published in January. This distrust also affects research.

Climate researchers have long encountered distrust, but researchers in other fields – particularly fields relating to immigration and health – are also encountering growing scepticism. Their research is often criticized on ideological or political grounds.

Fake science is an expression of this growing distrust of research. Fake science is alternative research that has not been subjected to a professional peer-review process. Such “research” is published in an alternative undergrowth of fake research journals that oppose the established research community on ideological grounds.

This trend is reminiscent of what is happening in the media, with the growth of the alternative media and websites disseminating fake news. These sources attack supposed left-leaning and “lying” established media. Like alternative research journals, alternative media sites are generally run by amateurs. Such people often fail to exercise editorial responsibility or comply with codes of editorial ethics.

How did we get to a situation where “the press is lying” and “research is rubbish”?

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt at New York University believes that while the storm of distrust is partly the result of growing economic inequality, it is also caused by the rise of social media, which is spreading alternative sources and mounting criticism on a large scale, making it more difficult to maintain confidence in established institutions, including those involved in research.

At the same time, it has become incredibly easy to publish and disseminate fake research. This year we are celebrating the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther nailing his Theses to the church door in Wittenberg. Innovative technology in the form of the printing press was decisive for the rapid spread through Europe of Luther’s uprising against established elites. Our equivalent of Reformation technology is of course the internet.

The existence of social media and the internet mean that fake science may quickly come to represent a serious threat. Research-based knowledge is a crucial collective global good. We are dependent on such knowledge in all crucial areas of society: health, education, technology and social development in general. Accordingly, it is extremely important to expose fake science before it becomes a major problem.

One example of fake science is the work of the self-styled Danish “researcher” Emil Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard has founded at least two open-access journals: Open Quantitative Sociology & Political Science; and Open Differential Psychology. Both journals appear reputable at first glance. In these journals, Kierkegaard and others in the alternative research community, publish articles “proving” that white people are superior to other racial groups. Like fake news, Kierkegaard’s research circulates in social media where it is superficially indistinguishable from research published in more reputable journals.

Today anyone can call him- or herself a researcher. It is also easier than ever to get something published and disseminate one’s own research. This short cut to publication is highlighted in the Norwegian report “National guidelines for open access to research results”, which reveals a growing number of illegitimate journals which use the open-access model to obtain money fraudulently. According to the journal Nature, more than half-a-million articles had been published in such journals in the years up to and including 2015. Alternative “fake science” journals use the open-access model, while lacking the stringent peer-review criteria applied by reputable journals, and operate along lines that are ideological rather than financial.

The dissemination and exploitation of fake science is a problem that will grow. To combat the problem, we must make genuine scientific knowledge as widely accessible as possible. Accordingly, we must raise researchers’ perception of the status of research dissemination. To some extent this is about awareness and a sense of responsibility among researchers, but it is also about how rapidly we can achieve a sustainable transition to open access and an open science system, and about how we structure incentives for researchers so that it becomes worthwhile for them to disseminate research and participate in the public debate.

In other words, fake science, like fake news, is a problem that needs a political solution. If Norway is to be a frontrunner for open access and open science, in accordance with stated government policy, then we must understand that fake science is a challenge we have to address.

- A Norwegian version of this text was first published in VG 3 May 2017: ‘Fake Science kommer for fullt‘

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext