National Security and Defense Research: The Imperative of Academic Freedom and Open Debate

Posted Thursday, 22 May 2025 by Kristin Bergtora Sandvik & Kenneth Arne Pettersen Gould

On 7 May, the Norwegian Defense Research Institute (FFI) hosted a Defense Research Day. The event focused on strengthening the cooperation between Norwegian researchers and the military sector. The context for the Defense Research Day is the changed geopolitical and regional security situation and the growing need for innovation and research to support Norway’s military defense. The Secretary of State for the Ministry of Defense, Marte Gerhardsen, emphasized the importance of removing barriers between the military and civilian sector, and that the shift towards supporting the defense sector was going to ‘hurt a little bit’ for both sides – as well requiring both sides to shift their focus and do things differently. To that end, the Research Council of Norway has been tasked with setting up a defense research portfolio.

On 8 May, the Norwegian Government launched the new national security strategy. The Strategy mentions ‘democracy’ nine times and emphasizes that academic freedom is fundamental to the rule of law and thus must be protected. At the same time, the Strategy states that research is central to competitiveness and internationalization and that ‘Responsible international knowledge cooperation requires that open research be weighed against security considerations at all levels in the knowledge sector.’ The Strategy also uses the word ‘critical’ in conjunction with raw materials, infrastructures, materials, societal functions and services – but not in relation to issues of academic freedom, open research, and public debate.

Largely lost in all of this is a discussion about the end goal. We argue that a broad public conversation is needed about the who, why, and how: who is involved, why, what is the nature of involvement, what are the consequences for Norwegian democracy and the research sector, and where do we want to go? What kind of peace and security is to be established, nourished and preserved through these collaborative efforts to support and develop the Norwegian military?

The starting point for writing this blog is our belief that academic freedom and open debate are not only central to the present and future of Norwegian democracy but also fundamental to successfully strengthening Norwegian security and defense. We are concerned about the lack of critical and dissenting voices – and about the absence of contributions from researchers outside the traditional defense research field concerning the analysis of security and defense policy issues. We invite more researchers to get involved and urge the Research Council of Norway to add the following three points to their agenda:

First, creating a separate system for the production and distribution of academic knowledge where contributions are kept secret from society at large may have unwanted but also unpredictable consequences. Constraints on publishing and sharing research data will affect individuals. However, more importantly for a small country like Norway, this may also have a chilling effect on scientific renewal and innovation. Generally, the number of experts and professionals is highly limited in any area of scientific inquiry and academic research. For example, there is a precarious lack of social science expertise on public security and defense procurement, despite the billions of taxpayer kroner being spent in these areas. If the Norwegian research community gets enrolled as defense researchers and embedded in structures of security clearances and classified information, the bureaucratic and economic drivers will reshape how academic freedom plays out in practice. It is vital for Norwegian democracy that academics can identify, analyze, and discuss the risk of corruption, inefficiency, incompetence, and waste without undue requirements of secrecy.

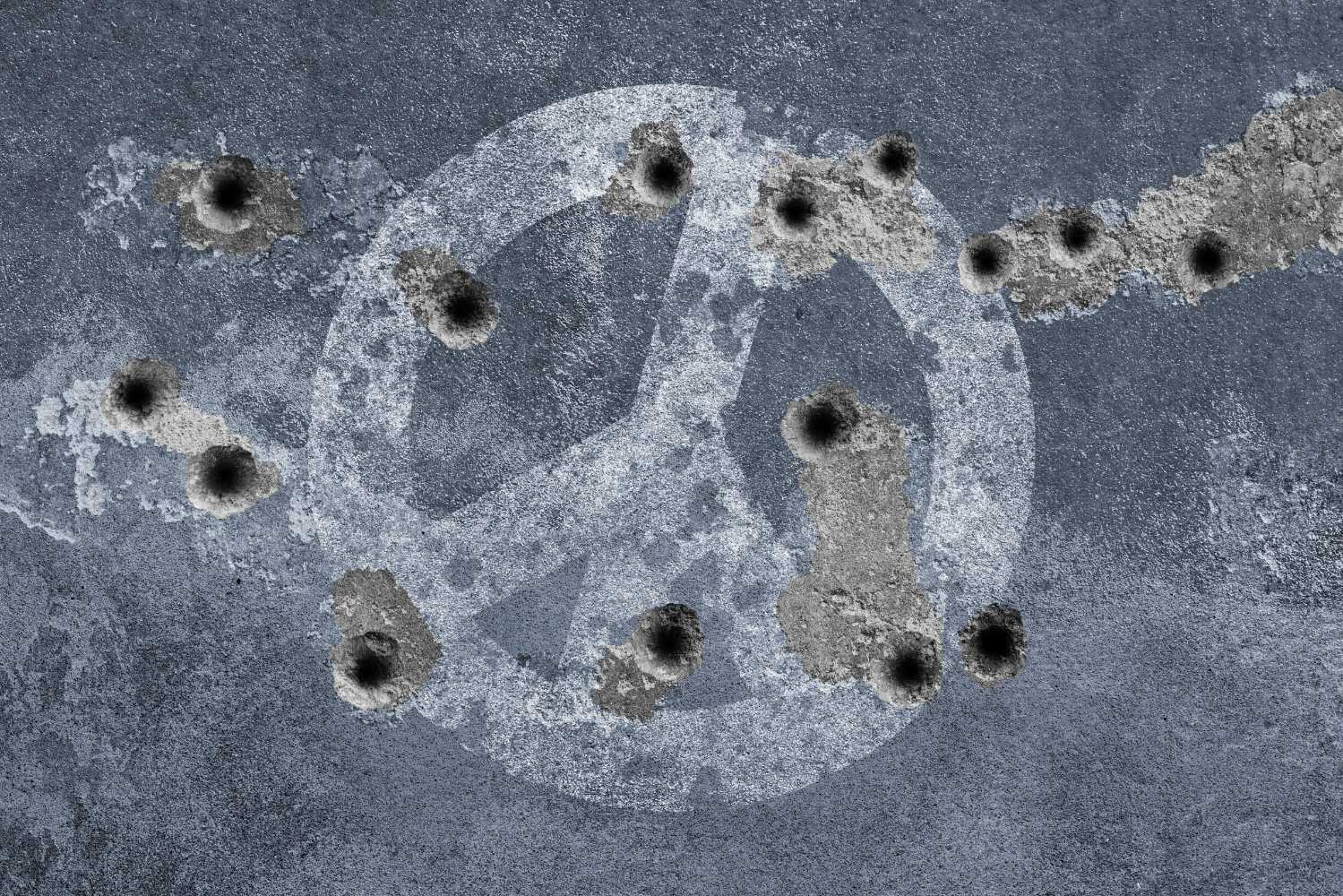

Second, nationally, no peace research agenda linked to the ongoing national security and defense developments has been articulated. Overall, there is a lack of ‘peace talk’ in the public domain. Perhaps surprisingly, there also seems to be a lack of interest from politicians and academics in engaging in public conversations about what peace looks like in the near to medium term and how we can protect, secure, and defend a peaceful society. The narrative seems to be that the country has been in a slumbering state of deep peace, but that we are now finally waking up. The deep peace slumber analogy is unfortunate because the reality is that peace does not emerge and settle by way of passivity and states of unconsciousness. Rather, peace emerges – and stays – through a multitude of deliberate, cumbersome, thoughtful, brave, tedious, costly, and willed actions, compromises, and sacrifices. Practically, this includes, among other things, solidarity and international aid, international cooperation and diplomacy, working against radicalization, respect for collective rules, and protection of minorities.

We have liked to call ourselves a peace-nation when bringing our troops and checkbooks abroad. Now we need a louder and more energetic domestic conversation about the role and play of peace in relation to the Norwegian militarization agenda and national security. This conversation should also be included – and supported – in the plans and strategies of the Research Council. We challenge the peace research community but also others to take this call for engagement seriously – now, not next year or when a new funding opportunity comes along. Across academia, this is no less than our shared core business: to think and talk about peace and about what an agenda for a peaceful Norway, Europe, and world ought to look like and the journey to get there.

Our third and final concern is about the relationship between society and security. In recent decades, we have learned that security is much more than technical defense, security and crisis management capabilities. Security is about, among other things, how we enable liberal democratic societies to live with uncertainty, and how we as individuals and collectively learn to respond to dangers and threats. At present, defense-oriented security is emerging as a kind of overarching security problematique and research gap to be plugged by defense and non-defense researchers alike, but without a clearly defined knowledge system to guide and provide content. Here, the Ministry of Education, Research and Innovation, the Research Council of Norway and the research sector must take responsibility for ensuring that we have sufficient diversity in research and innovation to meet a complex, uncertain and multifaceted threat landscape, without losing sight of what it is we want to protect.

In conclusion, free research undertaken by free academics is a core value of democracy: it should be open, transparent, and critical. There is a risk of setting in motion far-reaching shifts in knowledge production, which could undermine the liberal and free exchange of knowledge and of dissenting opinions. We call for a much broader public debate where more academics start taking capacity on defense-related issues more seriously, ask tougher questions, and work towards holding political, military, and commercial actors accountable. In our view, critical thinking and debate are also vital for the defense sector. Conversely, the absence of a critical debate is not a sign of patriotism but of weakness.

We are free academics. To remain so, we must learn more about defense, think more about defense – and talk more about peace.

- Kristin Bergtora Sandvik is a Research Professor at PRIO and Professor of Criminology and Sociology of Law at the University of Oslo.

- Kenneth Arne Pettersen Gould is an Associate Professor at the University of Stavanger