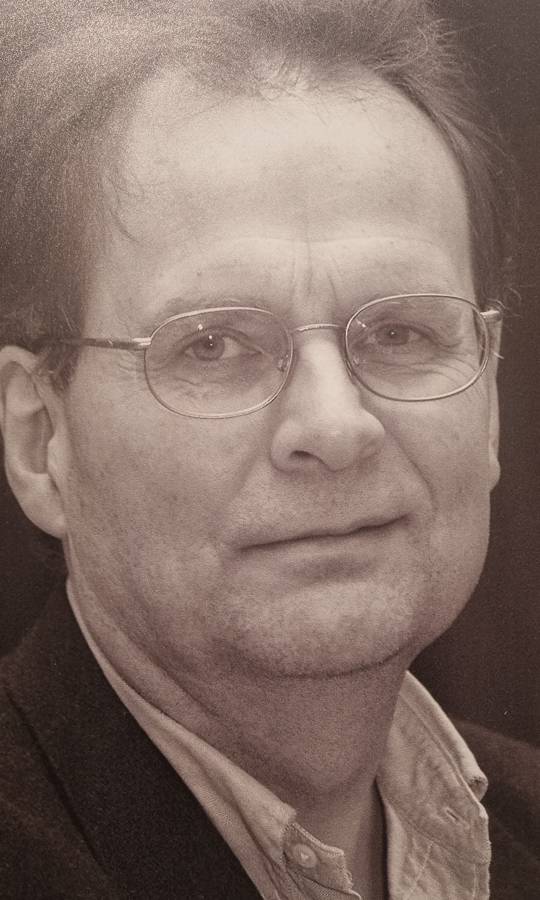

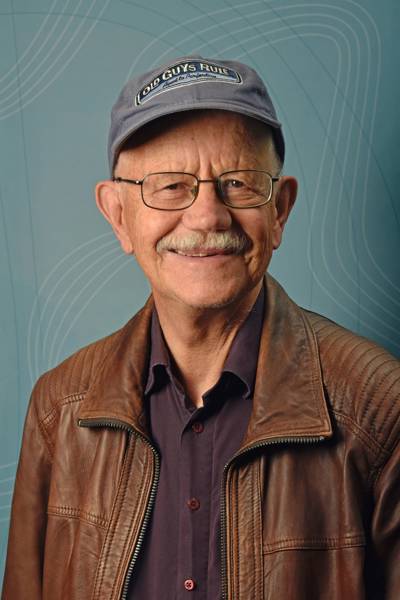

An Australian Viking has laid down his pen

Posted Friday, 22 Jan 2021 by Nils Petter Gleditsch

Andrew Mack, known to his friends as Andy, died peacefully in Vancouver on 20 January, just before his 82nd birthday.

Andy was best known in recent years for his work as the founder and editor of the Human Security Report, with four editions from 2005 to 2013, as well as several shorter Human Security Briefs.

Andy was a firm believer in academic rigor and adopted a narrow concept of human security rather than one that included all good things. He collaborated closely with the Uppsala Conflict Database Project and with PRIO. He sided firmly with Steven Pinker (and co-authored with him) in arguing for an optimistic view of the long-term decline of violence. He produced well-documented critiques on inflated fatality figures in the DRC and elsewhere. ‘It is not surprising that most people believe global violence is increasing. However, most people, including many leading policymakers and scholars, are wrong’, he wrote in Washington Post on 28 December 2005. But he also published novel – and sometimes controversial – interpretations of the data on issues like the apparent increase in global terrorism, the impact of war on health and economic growth, and on sexual violence in war.

Andy’s work on human security relied mainly on primary research done by others. But he was a discerning reader and critic of that research and he had an exceptional ability to communicate the findings and their implications to the policy community.

This arose from a long career that took him into academic posts in England, Australia, and Canada in particular, but also into key policy positions, particularly in the UN where he served for three years as Director of the Secretary-General’s Strategic Planning Unit. He drew on this experience in one of his most frequently cited articles, ‘Civil War: Academic research and the policy community’ (Journal of Peace Research, September 2002). The article argues that the academic conflict research community has far less impact on the policy community than the importance of its work deserves and offered a number of recommendations for how to improve the policy impact of conflict research.

His academic career started as an undergraduate student of sociology at the University of Essex in the mid-1960s. Here he met PRIO’s founder, Johan Galtung, ‘an absolutely spell-binding lecturer, enormously inspirational’, as he recalled some fifty years later when he was awarded an honorary degree at his alma mater. This was to shape his life and career although, like many of us, he would deviate from his mentor’s path on numerous occasions.

He went on to work at the Institute for Peace and Conflict Research in Copenhagen for six months. With Anders Boserup he co-authored a pioneering and influential book on nonviolence in national defense (War without Weapons, 1974), which offered a pragmatic approach marrying Gandhi with Clausewitz. It was translated into several languages. Although he never returned to Scandinavia to work full-time, he retained life-long friendships and collaboration with Scandinavia. The Human Security Report Project was supported financially by the Swedish as well as the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

As a prolific writer throughout his academic career, he contributed to a wide spectrum of issues in peace research and international relations. His most influential article is probably one that appeared in World Politics in 1975 under the catchy title of ‘Why big nations lose small wars’. Clearly influenced by the outcome of the Vietnam War, but drawing on a wide range of historical examples, he noted that the major powers involved were not defeated militarily, but rather ‘from the progressive attrition of their opponents’ political capability to wage war. In such asymmetric conflicts, insurgents may gain political victory from a situation of military stalemate or even defeat.’ … ‘Where the war is perceived as “limited” – because the opponent is “weak” and can pose no direct threat – the prosecution of the war does not take automatic primacy over other goals pursued by factions within the government, or bureaucracies or other groups pursuing interests which compete for state resources.’

Andy was not a quantifier. But he was an excellent interpreter and disseminator of statistical work. As he wrote in the 2009/10 Human Security Report: ‘Quantitative research can do two things that qualitative case-study research cannot. At the most basic level, cross-national data on conflict numbers and battle deaths can reveal long-term global and regional trends in the incidence and deadliness of conflicts that qualitative research cannot. Such descriptive statistics are the only means of tracking changes in the global security landscape – the major net decline in armed conflict numbers in the wake of the Cold War being a case in point. Statistical models … take the analysis to a different level and can reveal possible causal connections between the onset of conflict and such structural factors such as GDP.’ And his Essex interview ended with a strong encouragement to students to ‘try and learn those boring statistical techniques that are incredibly useful but very, very difficult to learn’.

A peripatetic scholar, he eventually settled in Vancouver for almost a full two decades and focused on his work on human security. This was also where he found his beloved wife, Laura.

In informal settings, Andy would address me and other Norwegian friends as ‘Vikings’. Ironically, I have always regarded Andy as a sort of Australian Viking. He was a tall man with a booming voice. His pre-sociology career included pilot training in the Royal Air Force, work for the British Antarctic Survey, and diamond prospecting in Sierra Leone! He was an avid sailor. Indeed, he lived on his boat for several years and had plans to sail across the Pacific with ‘a woman in every port’ (i.e. his wife), a project which he had to abandon for health reasons. Having invited him to join me in a spectacularly unsuccessful excursion in a friend’s sailboat in Oslo’s harbor (absolutely no wind that day), I could never persuade him to apply for the directorship of PRIO although the allure of the Stockholm archipelago might have made him consider SIPRI.

Andrew Mack will be widely missed by his many friends in Scandinavia. And, indeed, by scholars and practitioners worldwide who share his ambition to understand the world and to form a more peaceful future.

- You can find a memorial page for Andrew Mack at https://www.rememberingandrewmack.com/