Fragmentation and External Intervention Hamper Peace in Yemen

Posted Friday, 20 Sep 2019 by Maria Louise Clausen

The armed conflict in Yemen has grown increasingly complex as existing cleavages have become ever-more entrenched, and new ones are emerging.

The conflict in Yemen escalated in March 2015 when a Saudi-led military intervention complicated an already intricate internal crisis. Saudi Arabia’s intent behind the military intervention was to weaken Iran’s influence in Yemen and reinstate the internationally recognized president Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who had just been deposed by an Iran-aligned insurgency group, the Houthis.

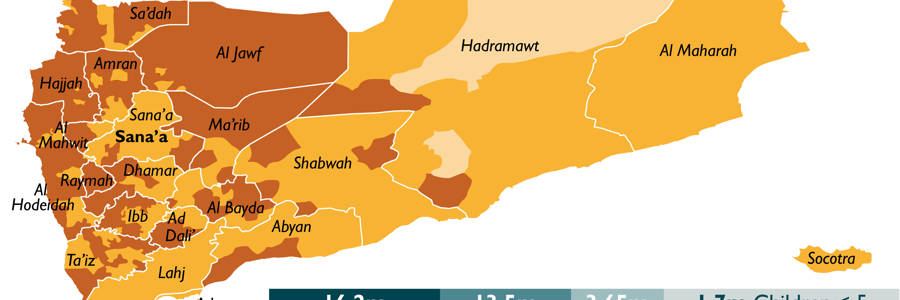

However, more than four years later the Houthis still control large areas of the country including the capital Sana’a. Meanwhile, the United Nations (UN) has struggled to achieve a breakthrough in the peace negotiations between the Houthis and the Hadi government.

In December 2018, a ceasefire agreement was reached on the three ports of Hodeidah, Salif and Ras Isa, as well as an agreement on a prisoner exchange mechanism and the establishment of a joint committee to reach an agreement on Taiz, a city currently divided between warring parties. The agreement renewed hopes for a broader peace settlement, but the implementation of the so-called Stockholm Agreement has since stalled.

Meanwhile, Yemen, which has never had a strong central state, has seen regional and local actors’ influence grow over the course of the conflict.

This process is most visible in the areas that are supposedly under the control of the internationally recognized president Hadi. In August 2019, the Hadi government’s lack of control on the ground became apparent when the Southern Transitional Council (STC), supported by troops trained and equipped by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), seized control of the interim capital Aden

Formed in 2017 and led by the former governor of Aden, Aidrus al-Zubari, STC is a part of a larger movement fighting for an independent South Yemen.

The struggle for independence has roots back in 1990, when the Yemen we know today was formed through the unification of North and South Yemen. Following the unification and a civil war in 1994, political power was centralized in the north.

This is important, as president Hadi was the vice president under president Saleh, who ruled a united Yemen from 1990 until he was removed from power during the Arab Spring.

Furthermore, Hadi’s current vice president, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, was one of Saleh’s most important supporters. He has close ties to Yemen’s Islamic party, Islah, a party often compared with the Muslim Brotherhood. There is a historical conflict between the Islamists – who are now a key part of Hadi’s government – and the Southern independence movement. To complicate the landscape further, Islah is considered a terrorist organization by the UAE.

The UN has so far upheld the narrative that Yemen’s political future may be solved through negotiations between the Houthis and the Hadi government.

In the southern regions, this is viewed as yet another example of how the south is continuously overlooked as power is centralized in the north. The present situation in the city of Aden supports the sense of being neglected. Despite being the interim capital, Aden is struggling with a lack of security and basic economic development.

The conflict in Yemen is often described as a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, but with fighting escalating in Aden the situation has become increasingly complex. Saudi Arabia still supports president Hadi and the idea of a unified Yemen, while the UAE, Saudi Arabia’s key ally in Yemen, supports the Southern Transitional Council that directly challenges Hadi.

However, just as it is problematic to reduce the conflict in Yemen to a struggle between a legitimate president and illegitimate insurgents, the situation in Aden cannot be solved by solely approaching it as a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Rather, the UN-led peace negotiations have to take into account that president Hadi has limited authority on the ground, and that large parts of the Yemeni population do not trust the UN-led negotiations to yield a political solution that will benefit all parts of the country.

Some may interject that the Yemenis must take responsibility for the future of their own country. This is something many Yemenis sincerely wish was an actual possibility.

Thus, the conflict between STC and the internationally recognized president illustrate central questions surrounding the role of the international community in handling complex conflicts, particularly as this relates to the international communities’ ability to integrate local perspectives into peace negotiations.

The role of the international community is accentuated by the fact that the Saudi-led intervention has been supported by the Global North. The United States has supported the intervention by assisting Saudi pilots in improving their targeting identification, providing refueling capabilities for coalition planes flying sorties over Yemen and extensive weapons sales. However, the potential humanitarian consequences of the military intervention are causing increased concern.

In April 2019, President Trump vetoed a vote from Congress on pulling out of the war. In England, a court has ruled the British arms export to the Saudi-led coalition illegal, as the considerations of upholding international humanitarian law were deemed inadequate.

Yet, so far, the Saudi-led military intervention has largely been able to operate with impunity.

Some may interject that the Yemenis must take responsibility for the future of their own country. This is something many Yemenis sincerely wish was an actual possibility.

The military intervention has created a humanitarian emergency that cannot be solved without considerable economic aid. And it cannot wait. This was the central message of UN Special Envoy to Yemen Martin Griffith when he recently briefed the UN Security Council on the situation. Yemen cannot wait.

- This text is based on an op-ed which was first published in Danish in Jyllands-posten 8 September 2019: Fragmentering og ekstern indblanding hindrer fred i Yemen.

- This text is a translation from Danish by Andrea Silkoset/PRIO.