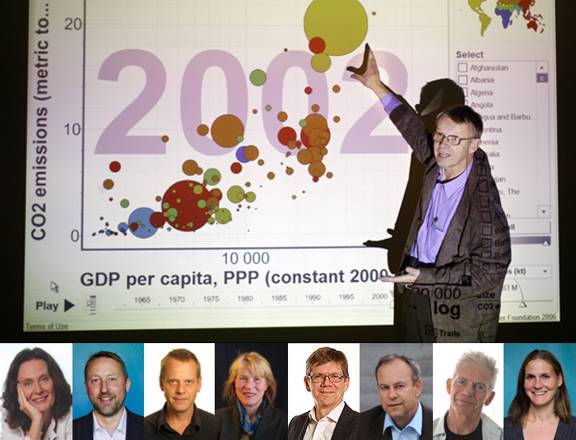

This memorial seminar is organized in honor of Hans Rosling, founder of Gapminder and world renowned scholar and inspiratory. The seminar is the second of the Oslo Lectures on Peace and Conflict and is organized by UiO Centre for Global Health, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), UiO Departement of Economics and UiO Life Sciences.

Let's discuss the challenges of exaggerated numbers, of identifying and reaching populations in humanitarian emergencies, and the implications for the politics of human progress.

Moderator

Scott Gates, Professor, PRIO & Department of Political Science, University of Oslo

Programme

13:00 Welcome

- Svein Stølen, Rector, University of Oslo

- Andrea Sylvia Winkler, Director, Centre for Global Health, University of Oslo

- Henrik Urdal, Director, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

13:45 Key note address: For a fact-based worldview

- Ola Rosling, Director & Co-founder of Gapminder Foundation

14:15 Presenters

- Gudrun Østby, Senior Researcher, PRIO: 'From the global to the local: How can we identify conflict affected populations?'

- Johanne Sundby, Professor, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo: 'Does access, coverage and utilization tell us anything about survival, or quality of services?'

- Karl Ove Moene, Professor, ESOP, Dept of Economics, University of Oslo: 'Political competition over life and death'

15:00 Panel discussion, Q&A and concluding remarks

15:30 Mingling and networking

with some light refreshments (we move over to Stallen, Professorboligen)

Exaggerations abound. For instance, armed conflicts and emergencies dominate media reporting, leaving us with the impression that the world is falling apart. In reality, there is much evidence to suggest that we have never lived in more peaceful times. In 1982, the global risk of dying in war was four times higher than in 2014, according to recent analyses. In 1972, it was six times higher. Just as it is difficult to convince people about the decline in war, we struggle to accept the great progress in health and prosperity. Generally, we live longer and better lives than we ever did. Yet, it is equally important to emphasize that not all parts of the world are progressing equally. Nor is development equal within countries and across groups. One important reason is that wars lead to a number of poor development outcomes, including low economic growth, increased infant mortality and fewer children in school.

Higher incomes can improve nutrition and lifestyles. Yet, the observed positive correlations between income and life expectancy do not reflect material improvements alone, but also the policies that higher incomes may induce. In many countries the benefits from higher growth basically go to the better off in society while the incomes of the majority of the population do not change much. The resulting increase in inequality can make politics less competitive, putting more weight on the interests of the rich and wealthy. As a consequence, policies may neglect basic needs of the majority for better health and service provisions. The interplay between growth, inequality, and politics can therefore break the positive link between material improvements and better health outcomes.

If we are to succeed in improving conditions for neglected populations, we need to understand the interplay between politics and economic conditions – and the conflict-development dynamics. A key to such understanding is improved data and better research tools. But sometimes, policy ambitions and advocacy produce ‘fake news’, potentially undermining our ability to act. A recent high-level UN report claimed that 60% of all maternal deaths take place in ‘humanitarian settings’, attracting well-founded criticism.[1] This unnecessarily crude calculation counts all maternal deaths in the 50 bottom countries of OECD’s state fragility index, failing to acknowledge that armed conflicts and emergencies rarely affect whole countries. The construction of exaggerated numbers not only leads to faulty decisions on where to prioritize scarce resources. It also contributes to the misinformation and humanitarian desensitization of the general public.

(1) Helena Nordenstadt & Hans Rosling , ‘Chasing 60% of maternal deaths in the post-fact era’. Lancet 388, October 2016: 1864-1865.

The Oslo Lectures on Peace and Conflict

Co-hosted by the University of Oslo and the Peace Research Institute Oslo, the series marks the mutual commitment of the two institutions to collaborate in ensuring Oslo's future as the leading hub for scholarly insight on peace and conflict, manifested in education, research, and interaction with policy-makers and practitioners, as well as engagement in public debate.