Crisis and deglobalization: Contributions of research and the role of researchers

Posted Thursday, 22 May 2025 by Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert

Humanitarian aid, development cooperation, migration governance and multilateralism have long been declared to be ‘in crisis’, but are currently experiencing unprecedented systemic shocks. Last week, we gathered researchers and stakeholders at PRIO for a collaborative discussion on what’s at stake and where we go from here.

First, on May 12, we convened a policy discussion addressing the questions of what now for the aid sector, and for Norway as a leading humanitarian donor (available to listen to here). Day two was dedicated to how we as researchers with long-term investments in each of these areas, can meaningfully contribute to ongoing exchanges, how current shocks affect our ability to conduct our research and what should be the role of researchers addressing these current issues.

The events also illustrated the vibrancy of the humanitarian studies community – in its broad and inclusive understanding, and the importance of continued engagement between policy makers, aid actors and academics. This blogpost summarizes the key take-aways from this discussion and the value of creating such spaces for slow and open thinking.

A vibrant interdisciplinary community

The discussion was interdisciplinary – not meant to try and re-constitute a specific sub-field of humanitarian studies, nor development or migration studies. It rather sought to illustrate from our different disciplinary vantage points - how these various shocks are impacting what we study and how we study it - here including anthropology, history, geography, law, political science, international relations, philosophy, and different fields of study, from media and journalism studies, Latin America studies, migration studies, refugee studies and humanitarian studies (forgive us if we forgot some, to be added!).

Through three panels, starting with the humanitarian system, moving over to the field of development aid and multilateral cooperation, and then over to the field of migration and refugee protection, several topics crystallized as key in order to think about how to address them, individually and as a collective of researchers.

From materiality to concepts

First, the discussion spanned from the materiality of aid – vaccines, ambulances, crutches, sanitary facilities, or even humanitarian logistics and aid trucks blocked at the border – to the physical meeting places where debates about the future of aid are taking place, to debates about concepts and narratives: how they matter, and how we as researchers have a role in critically examining which concepts are used, how they are used, and sometimes to introduce alternative and better concepts. In some research projects, known as the basic research projects, the freedom is ours to define and choose these concepts.

In more programme defined research, concepts and frames are more or less set: eg. in thematic calls of the Norwegian Research Council or the Horizon Europe calls of the EU, the problems to be addressed are framed, but still letting researchers identify how to approach them. In more commissioned research, problems to solve are identified more squarely by the donors. But across such projects, and more broadly, in policy discussions we contribute to, how can we meaningfully be aware of how concepts are used, sometimes critically questioning them and sometimes introducing better suited terms.

To narratives

As for the topic of departure, international aid: how do we meaningfully question established and reproduced narratives about what is for and about?

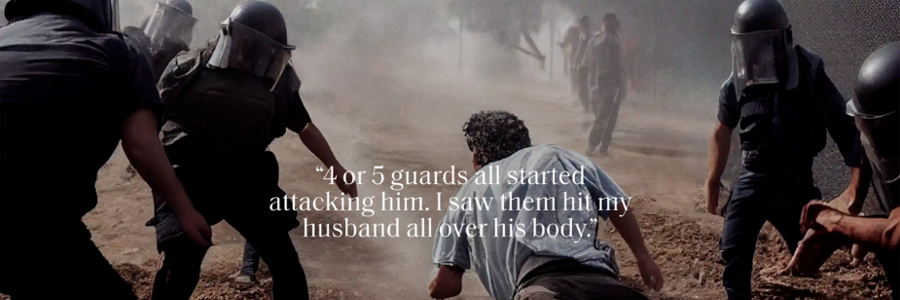

Concepts also make up broader narratives, which in turn matter for which crises get attention and not, and which kind of attention – as the security for Israel vs. humanitarian framing of Gaza and the Palestinian people, and the long historical trajectory of these narratives are important to recognize, even at a time where the humanitarian needs are simply unfathomable. In parallel with what sometimes appears as competing attention between Gaza and Ukraine, at least in terms of diplomatic, but also media attention, other crises are yet again “the most forgotten humanitarian crisis”: the two-year long war in Sudan only gets mentions along the lines of “what about Sudan” or “don’t forget Sudan”.

A major reason for why it remains out of sight on the global stage is probably the utter lack of a compelling narrative to convey to the world regarding what the war is about and what is at stake.

Seizing the moment

We also discussed the current ‘moment’ we are in. In the aid sector, this means thinking about how to build back better or think anew, and the idea of ‘back to basics’ of aid is often brought up. What does it mean for us as researchers? The idea of a ‘back to basics’ came up here as well, to go to the core and focus on the central topics of our research – and what matters the most. To use one concrete example, at a time where polarization around what colonization and decolonization means (and not), and where aid is contested from both a decolonial perspective and the far-right alike, perhaps this can be a moment to think critically about how these terms have been used, in order to refine and ‘think even better’ around structures of power. We also touched upon who ‘we’ are, as scholars based mostly in Norway, studying global issues and often conditions in the so-called Global South – vs. researchers with lived experiences of the same crises we study. It doesn’t need to be either-or: different perspectives are needed, from within and without. But our awareness of where we’re from and our privileges is always needed, while we continue to see how we can nurture good cooperation and dialogues.

Timeliness of research

In a world in shock and on speed, how can we ensure our research – otherwise relying on longer-term cycles of funding, projects, publications – remains timely and relevant? How to move from a sense of commentary of the present, to taking a step back and analyse – all the while arguing for our relevance to current societal debates? We don’t have an answer to this, but the question is very real and shared for many. When we are asked to comment on current affairs in the media for instance, we also all chose what we deem we are relevant to comment on, and what’s beyond our realm – but where we may point to other colleagues with relevant expertise – thereby also broadening the pool of public speakers. And while such commenting may feel like only reactions to the here and now, it is important to remember that such contributions build on wider insights and research. It is also important to keep in mind that we are managing a certain level of trust given to us as researchers, but that this trust cannot be taken for granted in increasingly polarized debates.

Structural conditions for research

Funding for our research, as well as funding for teaching programs, structures what we are doing research on, and within which conditions. A question to ask ourselves now, is how this will affect our recruitment of younger scholars, when funding even for senior positions becomes scarcer. Further, how will stricter border regimes affect our researcher mobility, both to travel for research, to organize visiting fellowships and invite in researchers from partner institutions – notably in less-resourceful countries. Programs such as Scholars at Risk exist and is a mechanism that could be further strengthened – for mutual benefits.

Researchers’ engagement and critical distance

We also discussed our roles as researchers contributing to public debates – from observers, analyzing with a critical distance, to sometimes becoming engaged in particular policy processes, to how we use our engagement more broadly and leverage our influence on public debates. There are perhaps no clear answers to these questions, but we should continue to discuss them, and as one participant put it, perhaps we should be ‘better at being comfortable with that discomfort’. Because that discomfort makes us continue to reflect and question. As we also continue to be aware of the crucial role of our researcher voices in public debates – and that the trust we have is not to be taken for granted.

Seen from the outside we may look like a group of academics agreeing on everything – and we certainly may agree on many fundamentals – we should also cultivate our ability to disagree, constructively and creating sound spaces for it. That is (and should) also be a fundamental contribution of academic institutions to society at large. At a time where US universities are being put to an ultimate test, it is important to be mindful of similar, although perhaps more subtle, tests to our own academic spaces. Finally, the importance of kindness was emphasized: we all, each in our ways, can contribute to making academia a safe, good and meaningful space to be in, even if we cannot immediately change the broader structures of it, and the world in turmoil around us. But little by little, we also hope to change that, each in our ways.

- Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert is a Senior Researcher at PRIO