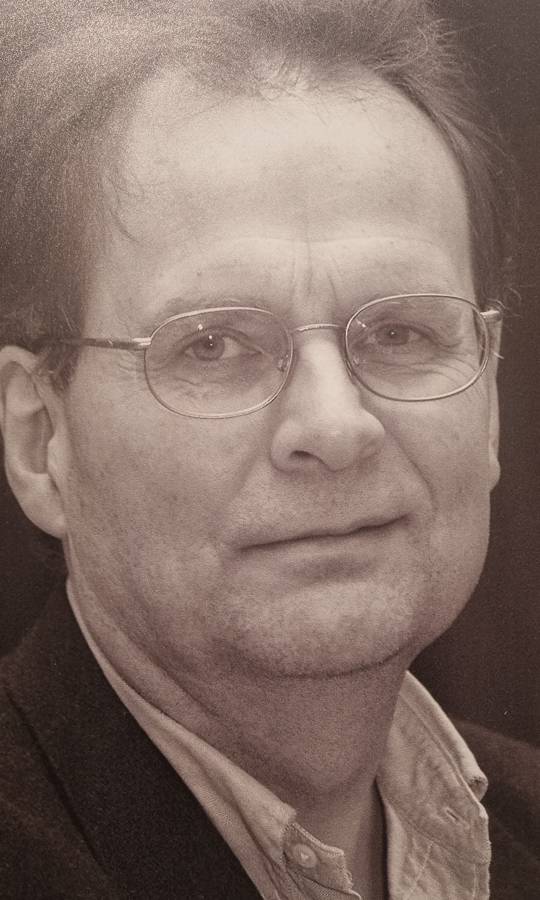

In memoriam: Arthur H. Westing (1928–2020)

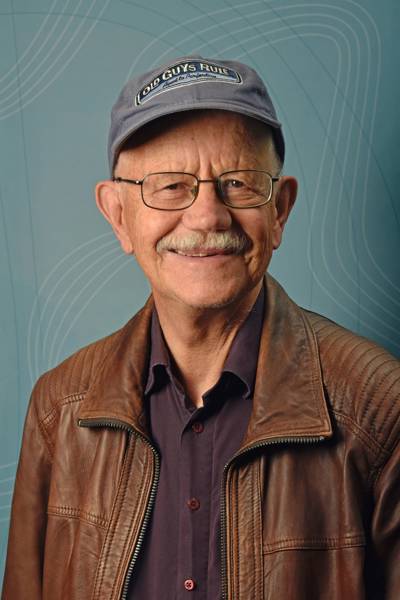

Posted Wednesday, 6 May 2020 by Nils Petter Gleditsch

Arthur Westing joined PRIO in January 1988. Sverre Lodgaard, who had worked at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) for the past six years, returned to Oslo to take over the position as Director of PRIO.

As a bonus, he was able to bring Arthur to Oslo at the same time, along with his project on ‘Peace, Security, and Environment’ funded by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). SIPRI’s loss was PRIO’s gain.

At PRIO Arthur edited a volume on Environmental Hazards of War, which dealt with the planned or inadvertent release of pollutants following the destruction of major industries in war. A year earlier, he had finished another volume, Comprehensive Security for the Baltic, also published in PRIO’s book series at Sage. This volume focused on security in the Baltic region as seen through the lens of an extended concept of security. Arthur did not invent the concept of environmental security. But his work was (and remains) one of the most thorough and thoughtful expositions of it.

When Arthur returned to the USA in 1990 (to retire, I thought — some retirement!), I had to take over the organizing of a UNEP-funded conference in 1991 on conversion and the environment which had fallen between the cracks. Some of the UNEP-funded conferences had to be held in the USSR in order to spend some of the non-convertible rubles in which that country had paid a major portion of its dues. I have to confess that I took on this project largely because I was fascinated by the opportunity to visit Perm (known as Molotov in my school days), a city closed to foreigners until just before our conference was held there. But my academic interest in the relationship between the environment and security arose from that experience and continues to this day.

Eventually, my PRIO colleagues and I came to focus more on the environmental causes of armed conflict than on its consequences. We have probably taken the work in a direction more critical of neomalthusian thinking than Arthur might have felt comfortable with. I found myself somewhat less pessimistic than Arthur on several issues discussed in his work, such as the risk that transboundary atmospheric pollution might lead to international conflict, that the quest for human security has become more elusive, that economic globalization may be harmful to environmental security, that environmental security is seriously deteriorating at the global level, and that global overpopulation remains our most serious problem. But if you want an intelligent defense of those propositions, you can do a lot worse than to consult Arthur’s work, for instance as published in the two volumes in Hans Günter Brauch’s Pioneer series (see end of post).

One of my most lasting memories of Arthur’s work at PRIO relates to his extreme attention to detail and accuracy, which the reader will soon discover in the two volumes just cited. Arthur found errors even in reputable collections of treaties and other standard works of reference. One of the few people who seemed able to live up to Arthur’s high standards of citations and references was his valued erstwhile colleague from SIPRI, Jozef Goldblat, who also became a PRIO Associate.

With an office right next to Arthur’s, I couldn’t help noticing the occasional outburst when someone did not meet his exacting standards. In one of my papers I inadvertently cited him as ‘Arthur F Westing’. This was not easily forgiven. Nor should it be.

But I thought even Arthur had gone too far when I learned that he was asking every author who had a direct quotation in a chapter in one of his books to send him a photocopy of that quote from the original publication. Surely this was going too far! Shortly thereafter I found myself in charge of an edited volume. PRIO’s discerning copy editor pointed out some language infelicities that appeared to have been committed by prominent writers – if one were to believe the lesser mortals who had cited them. Did they really say that? I was too embarrassed to ask the authors to send me copies of the originals, so I looked them up myself. And, indeed, there were numerous errors. Of course, scholars often copy quotations and references from previous articles they have read, so any errors get reproduced. Most of them are trivial, but once in a while there will be a disastrous ‘not’ too many (or one too few). Those of my colleagues at PRIO who think I’ve spent way too much time correcting details now know where I learned that modus operandi.

Many of my fruitful scholarly interactions with Arthur were linked to my role as Editor of Journal of Peace Research. Arthur published two articles and several short book reviews in the journal, and I took advantage of his presence to solicit referee reports from him on many occasions. In fact, over a 15-year period, he was among the top 5% referees in terms of the number of reports. I was particularly impressed by the fact that, as a matter of principle, Arthur always signed his reviews with his full name. Many authors, however committed they may be to transparency, are reluctant to do this because it exposes them to potential quarrelsome responses from authors who feel that their fine scholarship has not been sufficiently appreciated by the journal and its referees.

On factual academic matters, I was never able to catch Arthur out. My moment of triumph arrived years later when my son and I stayed with Arthur and Carol over a weekend in Vermont and went hiking with them in a local nature reserve that they had helped to establish, reflecting their environmental activism. This was in the fall and I suggested bringing along a basket for picking mushrooms. There are no edible mushrooms in that area, Arthur stated with some finality. Since my stubbornness matched his, I brought the basket along anyway. That evening we all had mushrooms at supper, and no one got sick. I was later told by Carol that no sooner had I left than Arthur went off to buy a mushroom field guide. This was in 1999, when he was 71. He hadn’t stopped taking in new knowledge then. He still hadn’t stopped at 92.

His commitment to the environment and the preservation of nature lasted literally until his death. A friend relates that for several days, Arthur and his wife Carol had been working on creating trails around their home at Wake Robin, in Shelburne, Vermont. Carol had been carrying the chainsaw, and Arthur was doing a lot of cutting, brush piling, raking, and clipping. On Thursday morning they went for a walk on the trails. They had stopped to rest on a bench along the trail, and while talking together, Arthur reached for his head, slumped over, and died.

- This text draws on an introductory text written in 2013 for Arthur Westing’s book From environmental to comprehensive security.

- See also: Arthur H. Westing – Pioneer on the Environmental Impact of War. This volume also contains a personal retrospective essay by Arthur Westing.

- Nils Petter Gleditsch is Research Professor at PRIO and Professor emeritus of political science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.