Peace and sustainability – two sides of the same coin

Posted Friday, 24 Oct 2025 by Nina von Uexkull & Halvard Buhaug

The world is severely off track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with the rise in armed conflicts a major cause. Peace (SDG 16) is not only a goal in itself—it is the foundation for all the others. At the same time, efforts to promote sustainability influence the prospects for peace in very different ways. They may help build stability, but if poorly designed, they can also trigger new tensions.

The world is going through turbulent times. More people die in armed conflicts today than at any point since the 1980s. The number of active wars is at a historic high. The effects extend far beyond the battlefield: millions are displaced, food and energy markets are disrupted, and investments in climate action and development are pushed aside.

Meanwhile, the 2030 deadline for achieving the 17 SDGs is approaching fast. On many targets, progress is stalled or even reversed. The rising frequency of armed conflict is a key driver of this regression.

Peace is a foundation for sustainability

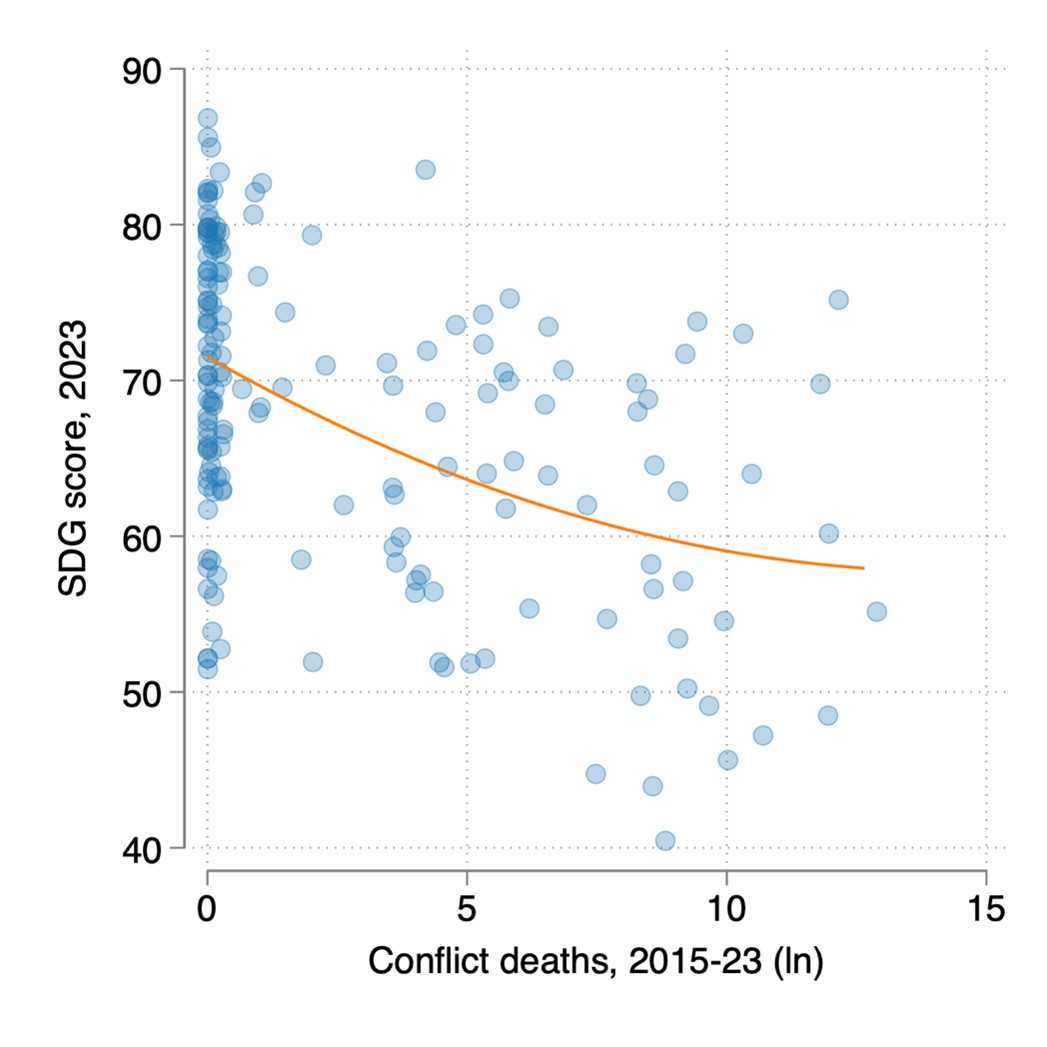

Where peace is absent, sustainability is undermined on every front. Conflict disrupts economic activity, destroys health systems, and forces children out of school. Social trust and democratic institutions erode. Forced migration, material destruction, and the loss of critical expertise and capital deepen the damage. As the figure below shows, countries affected by a major conflict consistently rank low on the SDG index (a ranking that measures countries’ progress toward the goals), whereas those scoring high have, almost without exception, avoided major conflict in recent decades.

This is why SDG 16 is about far more than just peace, justice, and strong institutions—it serves as the foundation for all the other global development goals. Without peace, lasting and inclusive development is impossible.

When sustainability interventions fuel instability

The link between conflict and underdevelopment may seem straightforward, but breaking the vicious cycle is far more complex. Sustainability policies can themselves trigger instability if poorly designed.

For example, cuts to fuel subsidies sometimes provokes mass protests. Hydropower dams and conservation zones may displace communities and strip them of livelihoods. Even well-intentioned environmental initiatives can heighten tensions, disproportionately affecting marginalized groups.

This does not mean the green transition (the shift to a low-carbon, environmentally sustainable economy) should slow down. On the contrary, it is essential for a livable future. But climate and sustainability measures must be tailored to local conditions, power dynamics, and social divisions. A climate measure that succeeds in Norway might have entirely different—perhaps destabilizing—effects in South Sudan.

Peacebuilding does not always strengthen sustainability

The same dynamic applies to peacebuilding. International peace operations reduce violence in many conflict zones, but this does not automatically lead to sustained development. Systematic studies suggest that their long-term impacts are often modest and short-lived.

In some cases, peacekeeping missions unintentionally weaken local institutions or fostered dependence on foreign aid, limiting resilience. Post-conflict periods can also bring a surge in resource extraction and deforestation, undermining climate adaptation and environmental sustainability.

In short, peacebuilding and sustainability efforts do not automatically reinforce one another. Real solutions need to be designed at their intersection.

Addressing knowledge gaps

Despite the clear links, we still know too little about how peace and sustainability measures can be designed to complement each other. In the commentary article underpinning this blog post, we highlight three knowledge gaps that stand out.

First, we have little evidence on interactions between peacekeeping and sustainable development initiatives. We need more research on how peace operations can lay the foundations for sustainable development, and under what conditions development initiatives in fragile settings reduce rather than intensify conflict. Current evidence is too thin to offer clear guidance.

Second, most impact assessments are judged by short-term results. For example, peace missions are assessed on immediate reductions in violence and climate measures on near-term emission cuts. Yet temporary gains do not necessarily translate into systemic change, and short evaluation cycles overlook cumulative effects—both positive and negative, which leads to a lack of long-term perspective.

Finally, research efforts are greatly hampered by a lack of reliable data from the ground. The areas most affected by conflict are often the least understood. Governments may restrict information, independent media may be absent, and fieldwork is often too dangerous. Indeed, some peacebuilding efforts inadvertently deepen inequalities or strengthen wartime economies (where conflict actors profit from smuggling, resource extraction, or aid diversion), downsides that might be avoided with the potential for deeper foresight from more reliable data and accurate information.

Less than six years

The clock is ticking. With fewer than six years remaining until 2030, the world can no longer afford to treat sustainable development and peacebuilding as distinct agendas. They are inseparably linked. Peace is the foundation of development, and well-crafted development interventions can, in turn, support peace.

In an era when war and environmental breakdown dominate global headlines, the need for collective action is urgent. What is required is not only political will but also evidence-based policies that recognize the interdependence of peace and sustainability. Without this, both agendas risk failure.

- Nina von Uexkull is Professor of International Politics at the University of Konstanz.

- Halvard Buhaug is Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

This Comment was originally published on the UNU WIDER Angle blog. It is based on a commentary article published in the academic journal One Earth on 19 September 2025.