Peace and good institutions save lives from floods

Posted Monday, 1 Dec 2025 by Paola Vesco, Nina von Uexkull, Jonas Vestby & Halvard Buhaug

In the first half of 2025 alone, devastating floods swept across Afghanistan, Nepal, Pakistan, the United States, and South Africa, killing hundreds and displacing more. The World Meteorological Organization warns that, as floods increase in intensity and frequency, many countries struggle to translate early warnings into effective response. Why do some countries succeed in minimising the human toll of floods, while others face repeated catastrophes? The answer lies not only in meteorological or economic conditions, but also in political ones.

In a new article published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, we present a systematic global analysis of how the quality of political institutions and exposure to violent conflict affect flood mortality. We use high-resolution satellite data covering more than 2,000 flood events worldwide between 2000 and 2018, combined with detailed estimates of population exposure, flood severity, and political and socioeconomic conditions in flood-affected areas. Our predictive modelling approach evaluates which factors best explain and predict flood mortality. This is a more suitable approach than traditional methods, as it checks whether the results hold up when tested on data the model has not previously seen.

The results are clear: countries with accountable and effective institutions and a prevalence of peace, experience substantially fewer deaths from flooding than fragile, conflict-affected societies - even after taking into account differences in countries' development levels to ensure a fair comparison. Among all factors, the breakdown of peace (measured by the severity of armed violence) is a robust predictor of flood mortality. Although often overlooked in disaster discussions, our study shows that peace and accountable institutions can reduce disaster risk at least as much as economic development.

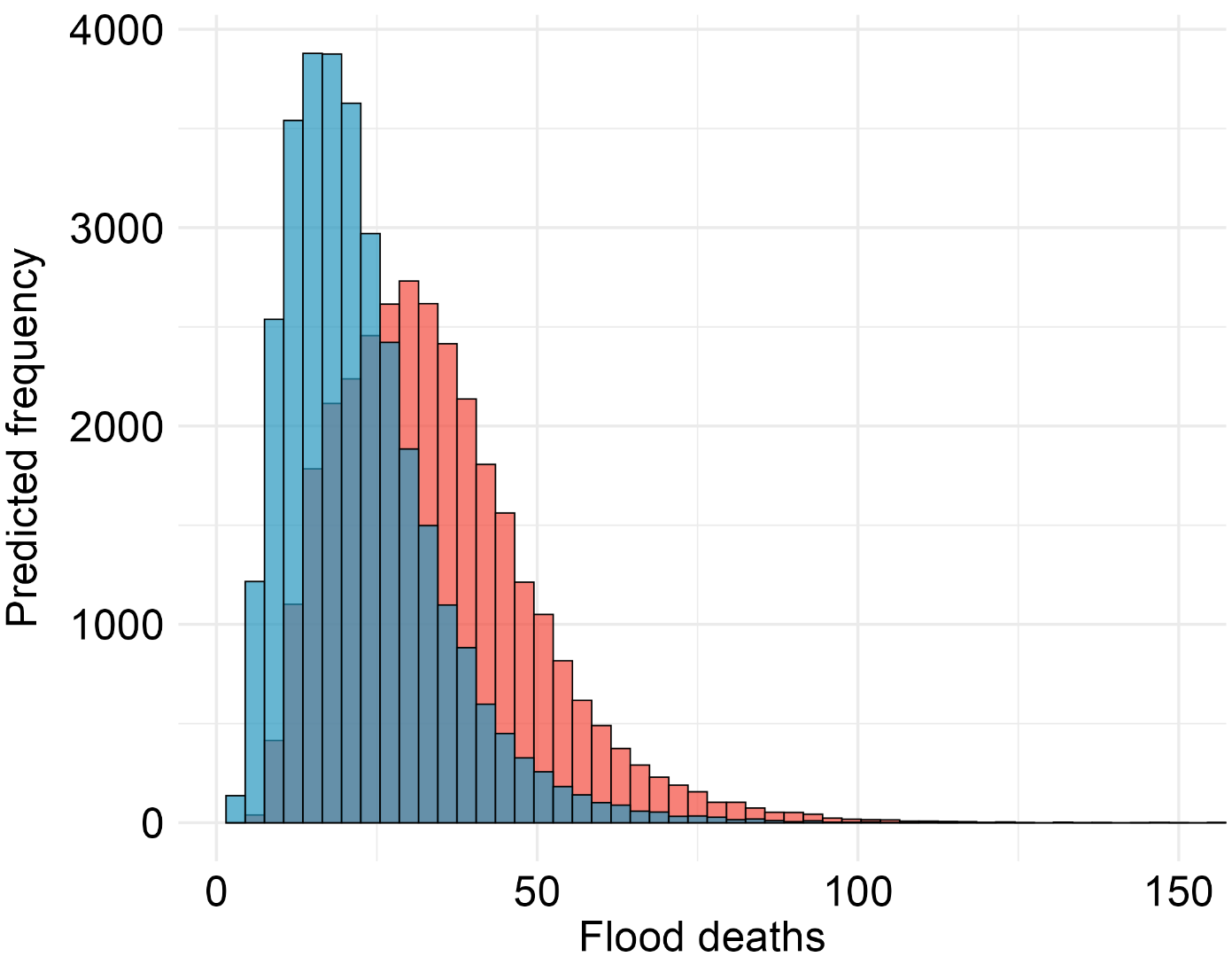

According to our analysis, if all countries had the same level of democracy, institutional quality, and peace as New Zealand, average flood mortality worldwide would drop by nearly half (Figure 1). Although this exercise is stylistic and needs to be interpreted with caution, achieving Sustainable Development Goal 16, which calls for peace, justice, and strong institutions, can be a viable strategy for mitigating the impacts of natural hazards.

The drivers of this relationship are complex, but the logic is intuitive. Accountable and inclusive institutions enable impartial governance and ensure that vulnerable groups are not left behind when disasters strike. Transparent decision-making and a free press provide checks on power, exposing corruption and mismanagement that can undermine disaster preparedness, while free and fair elections empower the public to vote incompetent leaders out of office.

Bangladesh is a successful example. Despite being among the world's most flood-prone countries, it has dramatically reduced flood mortality over the past decades, thanks to capable and accountable institutions that have invested in early warning systems, community-based preparedness, and equitable response. When Cyclone Amphan struck in 2020, millions were evacuated in time, and the death toll was just a fraction of that in comparable floods in previous decades.

Conversely, where decision-making is opaque, corrupt, or despotic, the poor and marginalised are often left behind. When Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar in 2008, poor and ethnically discriminated communities were excluded from relief operations. International aid was obstructed, and local assistance was hampered, as the government overlooked the ethnic minorities of the flooded Irrawaddy delta to weaken political opposition. This lack of institutional accountability and a long legacy of armed conflict contributed to one of the deadliest floods of all time.

In addition, in fragile and conflict-affected states, capacity is often low and international interventions are hampered. Governments struggle to mobilise resources, enforce safety standards and evacuation routines, and coordinate emergency responses. Where conflict breaks out, houses and assets are destroyed, social trust collapses, infrastructure maintenance deteriorates, and aid operations become dangerous or impossible. The consequences can be catastrophic. Two years ago, Storm Daniel struck Libya, killing over 10,000 people. Despite extreme rainfall, experts agree that years of civil conflict and fragile governance, which had left the city's dams poorly maintained, were primarily to blame for the scale of the disaster.

These examples are not isolated incidents. Since 2000, more than 1.8 billion people, roughly one-fifth of the world's population, have been directly affected by flooding. Climate change is intensifying extreme rainfall, and together with sea-level rise and glacial melt, it will expose an even larger share of the global population to flooding. At the same time, armed conflict fatalities are surging, and democracy across the world is backsliding. These trends are troubling in their own right, but our study suggests they also threaten progress in disaster risk reduction, increasing the likelihood that natural hazards will turn into deadly disasters.

Apparent data limitations mean that the actual life-saving effect of peace, democracy, and capable institutions is likely even larger than what our study could measure. To fully understand how political factors shape disaster vulnerability, we need more detailed information on the quality of local institutions, disaster planning, community-level adaptation efforts, and immediate response. Such granular data, if collected systematically and consistently, would allow researchers to identify what policy interventions are most effective in reducing disaster risk.

In turn, a clearer understanding of how political decisions shape vulnerability can help design effective strategies to mitigate the impacts of increasingly frequent natural hazards. While further research will help refine these findings, the core message is undeniable: we should not only look to technical and financial solutions in disaster risk reduction, but also dare to address political barriers to sustainability and resilience.

Paola Vesco is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Nina von Uexkull is Professor of International Politics at the University of Konstanz; adjunct professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, and Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Jonas Vestby is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Halvard Buhaug is Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and Professor of Political Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

- This commentary was first published by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.